Four Emerging Modes of Working in the Post-Covid Era

A new model for genuinely flexible and adaptive working

In the Aftermath of Covid-19: Changing Modes of Work

In the aftermath of Covid-19 here in the UK, people began to return to work, but work was not what it was before the pandemic.

In my work at the University of Brighton we attempted to come back to full face-to-face teaching as soon as possible, but the particular module I was teaching on creativity and business was allowed to continue as a hybrid model with one day face to face and one day online.

I had carried out some research during the pandemic and continue to do so, observing my own workplace as well as conversations with people in very different kinds of organisations.

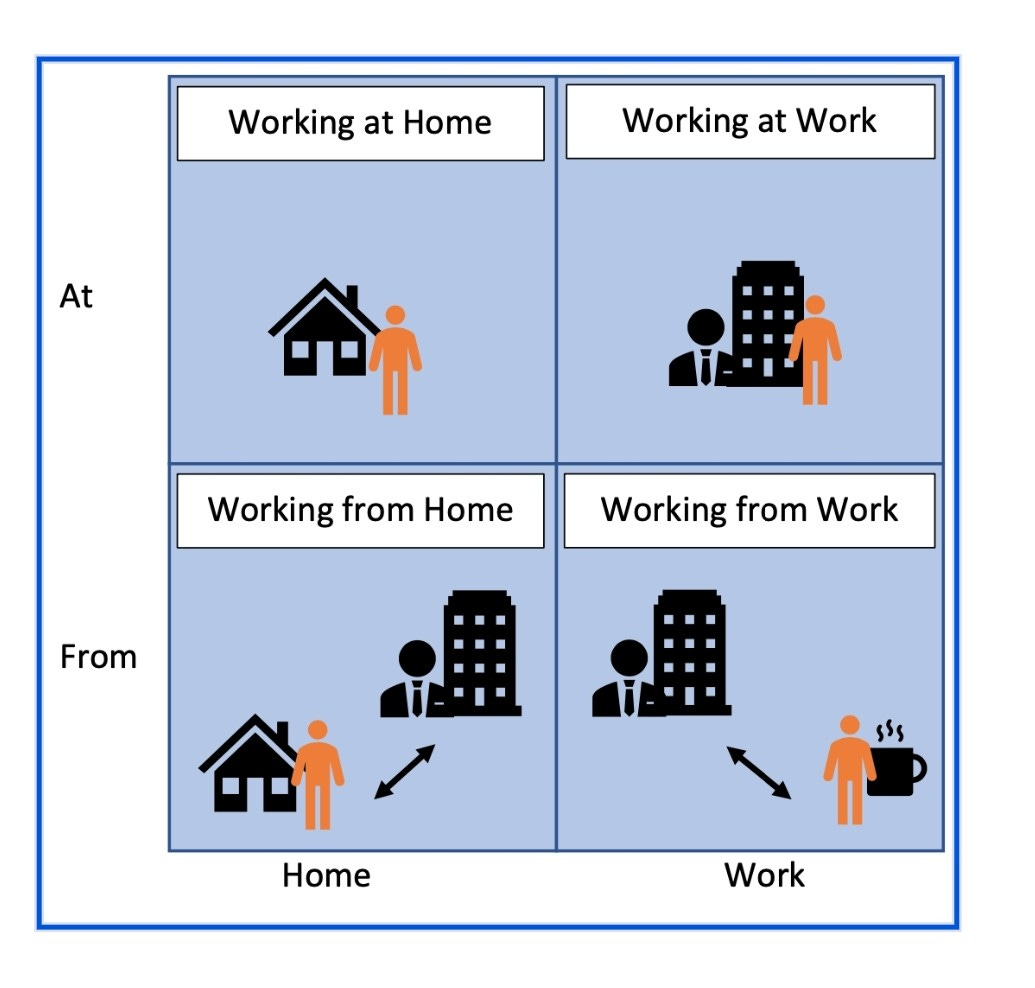

Those experiences and that research coalesced around a model that talked about four modes of working in the post-pandemic period that still pervade work today in different ways in different organisations and contexts.

Working at Work

The first of the four ways of working that I identified I call classically working at work.

This is the way of working that most of us are used to and many of us have reverted to, some full time and some in a hybrid or flexible way which was already in train before the pandemic for many people.

Working at work is when we are in our physical workplace and available to our colleagues and line managers and are following the specific elements of our role in the physical workplace. That workplace and its rules largely command how we work. So working at work is being physically present for a number of hours and our work is formally located in that place.

Working from Work

Working from work is a bit different. And this is the second aspect of the model.

When I work from work I have more or less autonomy about the way that I work. Some people who work from work arrive at the office in the morning at their physical workplace but might engage in other work that may not be the same as their routine work.

When I work from work, for example, I might come in to continue working on my book that I'm writing as an academic and I might lock myself away in a room with a ‘Do Not Disturb’ sign on it, and how I work will be very much then determined by me and I might be able or allowed to switch off my emails and be undisturbed.

Working from work might be that I'm not available to my colleagues but I'm meeting various clients in the work café. Once again though, the physical workplace is where I am working. This is not the routine formalised work that I normally do.

When we work from work we tend to have more autonomy.

Working from work might also capture how we work in a mobile way and so I might arrive at work and catch up on some emails and one or two meetings, but then work as a physical workplace becomes my base as I leave the building and more or less autonomously go and work in other places.

So I may be at work but I may not be available to people who would like to claim my time or formally, if it is acknowledged, that working from work is largely determined by my own autonomous decisions.

Mobile working therefore might have me using work as a home base physically but then moving into other modes of working.

Increasingly during the pandemic and afterwards, autonomous working has also meant that I go to the physical workplace because it might be that my home arrangements don't allow working at home, but I am in various online meetings and once again might book a hot desk in a closed room and I'm simply not available to the rest of my organisation in that physical workplace.

Working at Home

When I work at home this is the equivalent formally of working at work physically but I am simply not located in the physical workplace and, as happened during the pandemic, my workplace is located in my home.

This of course was a real struggle for some people forced to work at home during the Covid crisis because they might have simply been sharing a flat with no spare rooms with their family and there was a lot of making do and stress caused to families.

People were delivered technology at home and had to have IT support remotely. This kind of working has been happening for decades in some larger organisations as well as smaller ones and it can involve the company or organisation paying for a room to be dedicated as a working at home office.

For teleconferencing I remember some of the people I knew who were working in telecommunications had a dedicated room, received compensation for one of the rooms in their house being de facto an official workplace, and they were working at home but had, for example, to be wearing their work uniform and having certain types of decoration in the background.

But essentially when I work at home I am as available to my colleagues and engaged in formal working that is equivalent as if I was at the physical workplace.

Since the end of the pandemic some people have been allowed to work at home but the rules are very clear that the way that they work at home has to be formally the same as the way they work in their office or physical workplace.

Working from Home

Now finally the fourth element of this model is working from home.

I am based at home and I'm carrying out work but this is different from the formalised working at work, although elements of working from home might allow me to be available to my colleagues and my line manager for certain times.

But when I am working from home it is acknowledged that my home is my own domain and therefore it may be that family business has to take priority, that on a day when I am working from home I will have lunch with the family, take the kids to and from school, and even allow them some play time, or it might be that I switch off for an hour because I am at home and I need to be in for a delivery or there might be some social business to transact.

As in working from work I tend to have more autonomy here and command what happens in my place of work even though it is my home.

In the case of academia, sometimes when I tell my colleagues I'm working from home there is a definite ‘Do Not Disturb’ sign and on Microsoft Teams we set to busy or not available as we are doing some marking, working on a chapter of a book, or engaged in some other work that is not part of our routine.

Instead of doing this from a physical workplace it is clearly acknowledged on our calendar, for example, that we are at home, we are doing work, but this is not the same routine work where we become available to our colleagues or are engaged in more formalised practices that can be monitored by our line manager.

Balancing the Four Modes of Work

So this is complicated, I would suggest in creative and flexible ways-ways that mean we do not have to be in a binary mode of either being at home or at work.

Working at work and working at home enable us to engage in the organisation’s efficient processes and more formalised activities, and the only difference is that we are either physically present or working at our home location.

Working from work, which suggests more autonomy where the workplace is a base for many different activities, has a parallel with working from home, where we might be at home and engaging in different tasks that are not part of the routine. In both cases, our space-whether the workplace or the home-is respected, including home routines, family life, and sometimes the need to simply be away from work in the comfort zone of home to engage in more creative activities that do not require being disturbed by more routine work.

In my research I found that working at work and working from work were becoming confused, and this created stress in the organisation and in individuals.

There has always been a tension when I go to work to get my head down to do a larger task-for example writing a long report or analysing some data-where I need to lock myself away and not be disturbed, but where somehow people are knocking on the door and pulling my attention away from the immersive task. I end up getting drawn into the minutiae or the routine tasks that I really need to step away from so I can do this deeper task properly.

This is best managed through negotiation, openness and transparency, and where people feel committed and value the autonomy the organisation gives them to actually self-determine their work. So that when they are at home, they can make much more proactive decisions, preserve family life, as well as their own mental health, and be more efficient and effective because work is divided into different types of tasks that require different types of working environment.

Organisational Consequences

So what are the consequences of these four different modes of working?

One is an organisation’s need to be flexible around different working needs, both for the organisation itself and for those it employs.

With increasing evidence that Generation Z employees want work flexibility, the ability to work from home, choose the hours, but also to prioritise their well-being through different modes of working to match their energy levels and motivation, leaders of organisations need to make firm choices about whether they want to encourage these flexible modes of working or whether it is very clear that the contractual commitment favours one mode over another.

The extent to which that more limited approach will even be viable in a working culture increasingly dominated by the rise of AI-with generative AI potentially working alongside human workers and even replacing them-those jobs which require talent may involve a more competitive working environment in terms of recruitment.

In some ways, organisations may be able to call the shots on a preferred working style, where for example they make it clear that working for the organisation requires people to be working at work 100% of the time, and working from work becomes more tightly controlled.

But the opposite may also be true. Where a narrow or highly demanded skill set is required from employees, then the boot might be on the other foot-where employees get to call the shots and command their own preferred working style from the four modes of working.

It may also be important to skill up people working from home and working at home in order to enable them to be most effective and efficient in terms of the business need.

This may well be supported by smart technology, the internet of things, and assistive AI to enable people who are physically present at work to still integrate well with those who are not.

Technology may also become smarter in terms of allowing an employee who is based at home to flip skilfully, in an agile and fluent way, between working at home and working from home.

Similarly, effective and environmentally sound ways may need to be found where somebody who is working from work may transition to home and then back to the physical workplace easily.

If we find a way of making virtual working spaces, including metaverses, more effective than the initial stuttering start that these innovations have engaged in, then we may also find that we have another layer of complexity in which people are working at work, working from work, working at home, and working from home within virtual working environments and even metaverses.

So I may be physically at my workplace but may put on a haptic suit with much better quality headsets and be virtually back at my home where there is familiarity, and where I might have virtual interactions with my children and family.

This of course is science fiction at the moment and largely hyped up, but we need to be aware of it going forward.

Certainly, it may be possible to have virtual face-to-face relationships similar to gaming environments where I might virtually attend a meeting via my avatar.

AI developments may also make it possible for me to be in two places at once or even have several versions of me in different parts of the world, also working within one or more of the four modes of working.

There are clearly technical limitations to this at the moment and attitude surveys suggest that people are rather put off by these notions and possible futures in terms of different ways of working.

As things stand, I can be in all four modes of work and engage with digital technology to augment the physical experiences I'm having in one of those modes.

I might simply meet the family on Zoom, from my physical workplace, or I might simply have a different laptop that enables me to have an in-workplace experience whilst at home.

In my own view, this situation is being poorly imagined at the moment, with hype and science fiction having a tangible influence on poor choices around physical and home working.

Certainly, people can find that when they are in the mode of working from work or working from home, the modes of working at work and working at home impinge on the creative space or time out of routine work.

Basically, the threats from more formal modes of working at work and working at home start to claim status over the other more flexible and self-determined modes of working, and they become diminished and diluted and certainly play second fiddle to those two modes of working.

In this way, the four modes of working become unbalanced. The four modes are definitely better experienced-and we can get more efficiency and effectiveness from them-when they are in a conscious balance and when the choices we make enable flow between them to occur in the most effective way, enhancing and supporting well-being. Without this, we can experience increased sickness rates, with people going off with stress or simply working from home to hide from the other mode of working.

Historical Context and the Role of Organisational Culture

Conceptually, the four modes of working have coalesced around different organisational cultures, and these modes precede Covid by many, many decades.

The default of top-down hierarchical organisations has tended to favour and even demand full attendance, with clocking in and clocking out in the mode of working at work.

This was seen as the most efficient way and also the best way to control staff, with many organisations practising scientific management and measuring and controlling pretty much everything people did at work while working at work.

Only a select few had the autonomy to work from work, and this included mobile workers such as salespeople on the road.

In other industries, working from work was given to individuals who were essential to the business and demanded some autonomy in order to deliver on or even exceed their targets. These high performers were sometimes rewarded with that autonomy and were able to announce that they were coming in late and would be working from their home office.

This was rare back in the 1950s but it became increasingly prevalent, and theories of team working, collaboration and motivation-along with the rise of the telephone and other remote communication-allowed for experiments to happen where working from work became a genuine option.

As office design developed and meeting spaces as well as social spaces became more prevalent-as it was realised that motivated staff tended to perform better, and if the workplace was enriching people would tend not to go off sick-there was no excuse not to be in the office.

Because the office environment was beneficial, with free coffee, nice cafés, spaces to meet, people tended to default to the workplace even when they were not strictly carrying out routine work but were engaged in creative thinking and other forms of work that were less line-managed.

The work of Henry Mintzberg as he looked at different coordination mechanisms drew attention to this, as he outlined that ways to coordinate could move away from direct supervision and standardising work processes to ensuring people were skilled up for much more creative groups and were able to mutually adjust at their level in the organisation to solve problems more autonomously. This then favoured more flexible ways of working.

Why did I need to write a report locked away in an office with no natural light when I could go and sit somewhere else in the business, or even head out to a café or work from home?

Scaling up During the Pandemic

As remote technology became more prevalent, working at home became more of an option, where somebody was available initially on the phone and then on the mobile phone or via email on the internet, and then with the rise of social media and teleconferencing and video conferencing, working from home and working at home became more prevalent.

But this was all scaled up during the Covid-19 crisis, where being at home was the only option in most countries.

Quickly, working at work via this technology became the normal state of play, and many employees and managers suffered because their home arrangements were simply not suited to doing a nine to five job where they might only be in a living room as the only available room to work in or might have a desk in the kitchen.

Working from home also rose because organisations were concerned about well-being and wanted to make sure that non-routine work also got done, and so this paid respect to home arrangements and allowed people to self-define their working patterns-very much in the style described by Henry Mintzberg, where the coordination mechanisms were less top-down and formalised and people were trusted to self-organise as long as they met the agreed outputs (which Mintzberg refers to as standardisation of outputs), where we agree what the measure of success is but leave people to autonomously decide how they will work towards achieving these targets or goals.

This was more or less successful in line with whatever training and induction employees had, because some people's personality styles and skill sets did not lend well to deciding how to self-manage.

Others took to it like a duck to water, but many others were largely poorly trained in online Zoom or Microsoft Teams meetings and still were not able to self-organise, and so this led to the organisation losing control of employees and not really understanding how they were working.

So attempts were made to pull people back into the traditional working at work mode transferred to the home as working at home.

At its clunkiest, people’s laptops-especially if they were from work, and this became a demanded thing that you only use organisational-approved technology-were snooped upon, with measures put in place to ensure people did their hours and browsers were formally monitored to make sure people were accessing the websites that aligned with organisational goals and tasks.

Other organisations went down the route of training people to become self-organisers and tried to engender trust and an organisational culture based on self-management and the evaluation of self-managing teams.

These were Henry Mintzberg's coordination mechanisms based on mutual adjustment, standardised outputs and shared values.

If we can get buy-in to the values of an organisation to satisfy its customers in a genuine way, people can then be trusted to find the modes of working that will align with these goals without needing direct supervision and formal line management with various sanctions put in place if people do not do what they are told.

We are largely still in that place now where some organisations are managing this extremely well and others are doing it badly.

Others are reaffirming the physical workplace and refusing employees permission to work at home or work from home, whereas others have allowed one or two days a week where people can work in those modes at home, and others are still sticking with the idea that the four modes of working can be largely self-determined.

Technology is very more or less well used. There is certainly evidence that people use platforms such as Microsoft Teams and Zoom at the same minimal level they used to and are not really aware of the capabilities of these evolving technologies-the rise of AI, how to use AI for meeting recording, summarising and note taking, as well as how to put your camera on properly, manage backgrounds in accordance with organisational branding, and the general broader skills about when different types of technology need to be used in different contexts, and when a face-to-face meeting would be much more effective than a Zoom meeting.

I have written elsewhere of the evidence that when we work from home, for example, or work at work using technology such as Zoom to engage with people in other modes of work, this can lead to message replication, where people do not trust practical outcomes and decisions agreed and achieved virtually. This leads to the message replication of follow-up emails, phone calls, or even popping into the office of your line manager to check that decisions agreed at a Zoom meeting are actually genuine or have the genuine clarity and authority from that line manager.

So we have yet to fully trust the virtual technologies that can particularly support us in working at work and working from work, using technologies that can take us virtually out of the workplace-or working from home or working at home-that enable us to virtually leave the home and engage either with the office or people around the world.

Some people are clearly very good at it-what might be called naturals-but others find it clunky and bemoan current ways of working and wish they could simply have their old office back rather than a hot desk, and get back to the old days where they feel they were much more effective and happy.

Organisations don't tend to put the time in to innovate this and to ensure that this is developed and evolved in ways that maximise well-being and organisational and personal performance.

We need to put these conversations higher up in the priority list and actually have meetings that ask how well we are all working together in any or all of the four modes, and then address the new layer of complexity which will come-where we are not only in the four modes but we are either physical or virtual, whether at home or at work.

Mythos, Ethos and Logos: Aligning Organisational Identity

We need to carry out pilots, experiment and learn from both success and failure. There needs to be transparency in those conversations about what we are learning, and what has failed or succeeded, so people feel safe to experiment in different modes and particularly to either reject or develop the early skill set needed to engage with AI and engage in physical and/or virtual ways.

Then the model itself would develop not only into the four modes of working but into the hybrid mode of working that some organisations are already experimenting with-when we flip skilfully in and out, not only of the four modes of working but also in making choices around the physical or virtual mix.

If an organisation admits that, particularly since Covid but maybe even before that, it is in a state of organisational unclarity-even confusion-around how to lead a culture that harmonises with the different modes of working and is already tuning into a more mindful and skilful use of technology that will complicate this further, it must see this now as an opportunity for innovation. They need to open up the conversation.

Simple surveys might begin this conversation but this needs to be an engaging conversation in meetings across the organisation, as well as in the vision for the organisation itself in terms of what kind of business or organisation it wants to be, structurally and culturally, internally and externally.

It will need a digital and physical mythos. This is the vision for the future, which is currently more or less shared or more or less clear or more or less in existence. The mythos is in a way the collective dream for what the organisation is and how it will look going forward. It will capture what kind of organisation we want to be and currently are, and it will bring in pictures and stories and experiences of what it is to work in the organisation and when that is working more or less effectively-and how people are engaging with the emerging technology in the AI age.

Who are we, what do we want to be, what does our organisation look like when it is working effectively and happily, and what does it look and feel like when people are under stress and not achieving their own personal goals or are not properly aligned with the organisation's vision, as well as measures of efficiency and effectiveness?

The mythos can be a shared statement of values, but it has to be real-and real enough to guide behaviour. It may also emerge from flatter-structured organisations, where these stories and myths emerge out of the lowest levels of the organisational hierarchy, informing wiser decisions made upwards to the leadership team at the top.

Where organisations practise more flat-structure approaches and even use methods such as sociocracy, where they are essentially more democratic, the issue is the same and requires meetings, gatherings and conversations and opening space for crystallising around a flexible vision about how our organisation wants to work, is working, and how the four modes of working will play out now and in the future.

Focus groups, conversations, an item on the agenda that is more creative, diaries, journals, collaborative platform topic threads-there are many ways for this conversation to form part of our daily working. We can also open up space for input from our customers, suppliers and other key organisations or communities who have a stake in what we do.

Once a mythos is in train-because it is an ongoing conversation, refined and devolved-we then look to evolve more specifically our organisational ethos around ways of working.

Ethos refers to the codes of behaviours, the processes, what we write down, in the form of rules or guidelines. We will make decisions about the extent to which we will self-organise or still need more formal leadership. This may apply to the whole organisation or might need to be contextual and adaptive to different parts and functions.

Once again we have to decide the extent to which these behaviours are encoded in rules or the extent to which they are more value-based and that people can interpret the rules for themselves as long as the organisation’s mythos is clear, its destination and key performance indicators for that particular moment in time are adhered to.

What is clear is that one thing hasn’t changed, which is: if you police and force people, they tend to minimally comply; whereas if people feel bought into the mythos, they feel motivated, and their well-being is focused on a coherent link between their own sense of satisfaction and achievement and a wish to ensure the organisation that they love and work for achieves and even excels.

We can attend a Zoom meeting minimally, or we can attend a Zoom meeting fully engaged and wanting good things to happen and result.

Some people achieve that through a lot of self-motivation and self-organisation, where others want clear direction.

But what do we want overall for our organisational culture-to be one or the other, or an emerging mix of the two?

The organisational ethos is how we behave, and how we behave when we are being ethical is a way that accords with people’s sense of right and wrong. This can be embodied in the technology choices we make, how we manage information, how we manage people, and how we engage internally and externally-and most of all, how we have defined the best ways to use our time in ways that maximise performance and well-being.

Once we have our mythos and our ethos aligned-which has to be authentic and genuinely bought into and understood-we move into our logos.

This sounds like a strange word and it is used very specifically here, not in any mystical way. In some ways, the logos is the scientific word. It is the way that we measure and know whether we are achieving an aligned mythos and ethos.

These might be performance indicators, but when they are placed and top-down controlled with sanctions and consequences, that can backfire-and there is evidence that it does with Generation Z and the emerging cohort who tend to like to self-manage or to have very clear leadership and measures that they are actually bought into, rather than feeling that they are being policed.

So we might create self-measures, and the rise of AI might simply give us objective feedback about how we are doing and recommend ways to improve.

Using AI and other digital innovations with us as the master and the determiner of what happens is likely to be more effective than using AI to snoop on us and even take over from us when we are failing, without our wish for that to happen.

But there are top-down organisations which will use AI in a very common control-focused way that might well work.

In all cases, the logos has to align and not conflict with the ethos and the mythos.

Dissatisfaction will arise when we see a mismatch between the codes of behaviour, how they are measured, and the values of the organisation.

When we say we are committed to sustainability but then increase the level of fossil fuels we use, people are not aligned.

Working from home therefore becomes an opportunity, as does working at home, for people to minimise their relationship with a physical workspace.

Ultimately, when the conversation opens up-and it will always be unclear and messy at the start and need updating-between an aligned mythos, ethos and logos, we start to create an integrated organisation, where people tend to associate with each other in positive ways, using the technology mindfully and making authentic and helpful decisions about the format of working and the emerging hybrid ways of working using the technology that is available.

Organisations in the future, in an increasingly uncertain world-and that uncertainty has been growing for decades-will be better if the organisation is flexible, a conscious business or organisation, finding the right balance between coordination and control in traditional ways, and self-management, community and mutual respect, with an ability to creatively move between different ways of working as needed by the organisation and the individual in terms of their propensity, ability, and commitment to helping the organisation achieve its mythos.

Five Final Questions

In your organisation, who truly decides what mode of working is acceptable, and why is that power not more democratically distributed?

Are so-called flexible policies actually reinforcing control in subtler ways, under the guise of autonomy?

What part of your organisational culture is resisting the alignment of mythos, ethos, and logos-and what unspoken values are maintaining that resistance?

How are you preparing your people-not just technically but ethically and emotionally-to navigate the new hybrid futures of work?

If your staff feel the most creative, safe and effective when working from home, why are you still investing in office spaces rather than investing in them?